12 Surprising Reasons Your Joints Ache in the Cold — The Science Explained

Most of us have a weather-linked ache that shows up when the thermometer drops. That sensation can be confusing: sometimes you notice stiffness before the rain hits, or ache in the knees that wasn’t there a week ago. There’s no single cause. Instead, several biological processes respond to temperature and pressure changes, and when combined they can make joints feel stiffer, sorer, or slower to move. This article walks through a dozen distinct reasons your joints may complain when it’s cold. Each item explains how the body reacts, what the science says about that reaction, and what small changes you can try at home. We’ll lean on physical-therapy experts and peer-reviewed findings when available, and keep the language practical and friendly. If you live with arthritis, prior injuries, or long-term pain, you may recognize many of these mechanisms in your own experience. That’s okay. Learning how cold affects nerves, fluid, muscle, and tissue can help you pick targeted steps that reduce discomfort and keep you moving. By the end you’ll have a short list of actions — from gentle movement to keeping joints warm — that align with what the science explains about why the cold makes joints ache.

1. Ion channel sensitivity in nerves

Nerves carry temperature and pain signals through tiny openings called ion channels. When tissues cool, many of these channels become more likely to open. As the Research Agent found, physical therapists note that a drop in temperature can “excite the ion channels” and increase the electrical messages sent to the brain. That helps explain a familiar pattern: you can feel more pain even before obvious swelling or redness appears. Consider the nervous system’s scale: Memorial Hermann clinicians point out there are roughly 400 nerves that would stretch about 45 miles end-to-end, all wired to sense pressure, temperature, and pain. Cooling makes more of those pathways likely to fire, which raises overall sensitivity. Practically, that means warmth and gradual movement can calm the system. Covering an achy joint or doing a few slow range-of-motion exercises warms tissues and can reduce the ion-channel-driven spiking of pain signals. If nerve sensitivity feels extreme or is accompanied by numbness or weakness, check in with a clinician for targeted testing and treatment.

2. Synovial fluid thickening makes movement feel stiff

Inside most joints sits synovial fluid — a slippery substance that reduces friction and nourishes cartilage. In colder temperatures that fluid becomes more viscous, acting a bit like cold motor oil. When viscosity rises, joint surfaces don’t glide as smoothly and range of motion can feel reduced. That mechanical stiffness is different from sharp inflammatory pain, though the two can overlap. The practical takeaway is simple: warming the joint and gentle motion help the fluid thin slightly and restore glide. Short walks, slow joint circles, or a warm shower before activity can make movements feel easier. For people with existing cartilage wear, thicker fluid amplifies the sensation of roughness during movement. Regular mobility work and gentle strengthening support muscle control, which spreads load more evenly and reduces grinding. If stiffness limits everyday tasks despite consistent home care, a medical review can assess cartilage health and discuss options like injections or specific physical-therapy plans tailored to your joint mechanics.

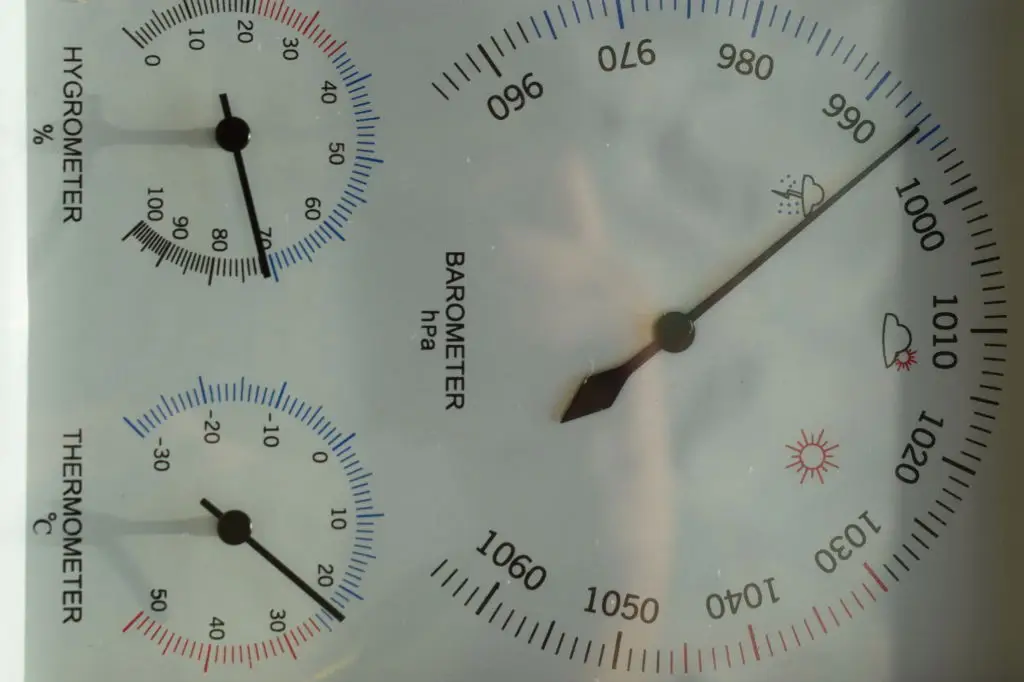

3. Barometric pressure shifts change how tissues signal pain

Changes in barometric pressure often precede storms, and those pressure shifts alter the force around our bodies. When external pressure falls, structures inside the body expand subtly. Pressure-sensitive receptors in tissues can detect those small changes, and for some people the altered mechanical environment increases pain signaling. Research reviews describe moderate evidence linking pain with temperature, barometric pressure, and humidity, so this isn’t just folklore. Historically, physicians have noticed weather-linked complaints for centuries; modern studies aim to measure and explain the effect. The result is a common experience: aches that feel worse before or during windy, low-pressure weather. If you track symptoms, you may spot a pattern tied to weather charts. Practical strategies include keeping joints covered and moving during low-pressure weather, since warmth and activity reduce receptor sensitivity and improve circulation. While barometric effects are out of your control, lifestyle steps can blunt their impact on daily comfort.

4. Muscle tightening and reduced blood flow raise discomfort

The body protects core temperature by tightening muscles and narrowing blood vessels in the skin and limbs. That vasoconstriction preserves heat but reduces blood flow to muscles and joint tissues. Reduced circulation can mean less oxygen and slower removal of metabolic byproducts, which makes tissues feel tighter and more prone to ache. Additionally, tightened muscles pull on tendons and joint capsules, changing alignment and increasing mechanical strain. The combined effect is a stiffness that feels both muscular and joint-related. Simple actions reverse these effects: layer clothing, use heat packs, and prioritize gentle warm-ups before activity. When muscles are warm they relax, circulation improves, and the mechanical load on joints eases. For persistent muscle-related pain, a physical therapist can show targeted stretches and strengthening to reduce chronic tightness. Those exercises help circulation and increase resilience, making cold snaps less likely to trigger sharp discomfort.

5. Cooler tissues change cartilage and connective-tissue elasticity

Collagen-rich tissues — ligaments, tendons, and cartilage — are temperature-sensitive. Cooler temperatures reduce their elasticity, making them stiffer and less able to absorb load smoothly. When connective tissue stiffens, joint movement requires more force and feels less fluid. Over time, repeatedly loading stiff tissues can increase micro-irritation and the perception of soreness. An everyday analogy helps: rubber becomes less flexible in the cold and snaps back slower; soft tissue behaves similarly. That’s why warming up matters: a deliberate, progressive warm-up raises tissue temperature, increases elasticity, and spreads forces more evenly across the joint. For older adults or people with prior joint injury, gradual mobility and moderate strength work are especially helpful because they improve support for the joint and reduce harmful strain. If stiffness persists despite a consistent warm-up routine, an evaluation can check for structural issues contributing to loss of elasticity.

6. Thicker fluid and stiff tissues raise joint friction

When synovial fluid thickens and surrounding tissues stiffen at lower temperatures, the internal joint surfaces can experience more friction during movement. That grinding or “grindy” feeling is a mechanical result, not necessarily a sign of new damage. Still, the extra friction can aggravate sensitive nerve endings in the joint and lead to an increased perception of pain. Distinguishing mechanical friction from inflammatory flare matters because treatments differ: warmth, lubrication through movement, and muscle support reduce friction, whereas inflammatory pain may benefit from anti-inflammatory strategies under medical guidance. To reduce friction at home, focus on smooth, controlled joint motion and strengthening muscles that help the joint track properly. Low-impact activities like swimming, stationary cycling, or gentle resistance training are practical choices that promote joint glide without heavy pounding, especially in colder months.

7. Humidity plus cold often makes symptoms worse

Humidity by itself shows a weaker link to pain than temperature or pressure, but when the air is both cold and wet the combined effect often amplifies discomfort. High relative humidity can make tissues feel heavier and may alter how pressure waves move through joint capsules and soft tissue. Physical therapists in the research found that humidity’s effect appears stronger in colder conditions. For people with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, that cold-and-wet combo often coincides with a noticeable uptick in stiffness and soreness. Managing exposure is practical: wear breathable yet insulating layers, use waterproof outerwear to stay dry, and consider indoor humidifiers in very dry but cold climates so extremes are buffered. Tracking symptom patterns with local weather can help you anticipate tougher days and plan lighter schedules or extra self-care on those days.

8. Chronic joint conditions and aging increase sensitivity

People with chronic joint conditions such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, or long-standing injuries tend to be more weather-sensitive. Aging brings structural changes to cartilage, tendon quality, and circulation, which reduces the joint’s buffering capacity. That combination makes older adults more likely to notice cold-related aches. Large weight-bearing joints — especially knees and hips — often report greater symptoms because they continually handle load and movement. The practical conclusion: prevention and maintenance matter. Regular, modest exercise that includes strength, balance, and mobility reduces the mechanical stress that amplifies weather effects. Simple home practices like keeping warm, pacing activities, and breaking tasks into smaller steps also help manage daily function. For people with diagnosed inflammatory conditions, staying on prescribed treatment plans and checking in with a rheumatologist when patterns change are sensible steps.

9. Inflammation and immune signaling can shift with cold exposure

Cold exposure can influence inflammatory pathways and immune-cell behavior in subtle ways. While clinical results vary, mechanistic studies suggest that temperature changes alter levels of certain signaling molecules that modulate inflammation. In people prone to inflammatory flares, those shifts can move a joint closer to symptomatic thresholds. The research landscape is mixed but supports a modest role for inflammation in weather-linked pain for susceptible individuals. Practically, anti-inflammatory measures aligned with medical advice — such as medication as prescribed, targeted exercise, and weight management — reduce baseline inflammation and therefore lower the chance that a chilly day will trigger a noticeable flare. If you notice a clear change in swelling or systemic symptoms like fever alongside weather-linked pain, seek medical evaluation promptly to rule out infection or active autoimmune flare.

10. Central nervous system amplification and anticipatory pain

Pain isn’t only local. The central nervous system can amplify signals from the body so that minor inputs feel larger. If you’ve learned that cold predicts more pain, your nervous system may begin to anticipate and heighten those sensations. This anticipatory or centralized amplification explains why some people feel pain before weather changes are obvious. The ion-channel sensitivity described earlier links to this process because more frequent peripheral signals prime the central system. The good news is that central amplification is modifiable. Graded exposure to activity, mindfulness-based approaches, paced movement programs, and consistent gentle exercise help the nervous system recalibrate. For persistent central sensitization, multidisciplinary approaches — including physical therapy, cognitive strategies, and medical support — can reduce the intensity of weather-linked pain over time.

11. Practical self-care steps that target the science

When you understand the mechanisms, practical steps follow logically. Keep joints warm with layers and heat packs to reduce ion-channel spiking and improve tissue elasticity. Move gently to thin synovial fluid and restore glide; short mobility sessions three times daily are a low-burden habit that helps. Strength training supports joint mechanics, reducing friction. Stay active with low-impact choices like walking, cycling, or water exercise to boost circulation without inflaming joints. Use topical heat before activity and a warm shower after to relax muscles and improve blood flow. If swelling or inflammation is present, follow medical guidance about anti-inflammatory treatments or medications. Small, consistent changes are realistic and sustainable; they don’t require dramatic time investments but they do build resilience that makes cold snaps easier to tolerate.

12. When to get checked: tests, referrals, and treatments

Most weather-related aches improve with home strategies, but certain signs warrant medical review. Seek care for sudden severe swelling, intense pain with fever, rapid loss of joint use, or new numbness and weakness. A clinician can evaluate for conditions that need specific treatment, order imaging if structural problems are suspected, or refer to rheumatology for inflammatory disease workup. For chronic degenerative changes, treatments include tailored physical therapy, medication adjustments, and, where appropriate, injections or surgical options. A careful history that documents weather patterns and symptom triggers helps clinicians tailor treatment. The goal is practical: reduce symptom burden, preserve function, and target the underlying reason a joint is extra-sensitive to cold.

Wrapping up: What the science means for your daily life

Cold-weather joint pain reflects multiple, overlapping processes: nerve excitability, thicker joint fluid, pressure shifts, muscle and blood-flow changes, altered tissue elasticity, and an individual’s medical history. Each mechanism offers a practical point of action. Warming and gentle movement address ion channels, fluid thickness, and muscle tone. Strength and mobility work support joint mechanics and reduce friction. Staying dry and layering helps blunt humidity and pressure effects. If you live with a chronic condition, coordinated care and consistent self-management lower the odds that a chilly stretch will derail your week. Most importantly, small, steady habits matter more than dramatic fixes. A short warm-up, a heat pack before a walk, or a five-minute mobility routine can ease daily life and keep you active through colder months. If you notice new, severe, or rapidly worsening symptoms, reach out for medical evaluation so you can get targeted care and return to the activities that matter most.