Reasons Your Hands and Feet Feel Cold First — and What to Do About It

Feeling your fingers and toes go cold long before the rest of you is a common—and often confusing—experience. Your body has a simple priority: protect the organs that keep you alive. That means when the thermostat drops or you encounter a stressful moment, your nervous system tightens the tiny vessels in your hands and feet so warm blood stays near your heart and lungs. This reflex keeps the core safe but leaves extremities feeling chilly. Most of the time this response is harmless and short-lived. Sometimes, though, persistent or painful coldness points to medical problems that deserve attention. In this article you’ll find clear explanations of how temperature control works, common causes ranging from Raynaud’s to thyroid issues, the tests doctors use, and realistic steps you can take at home. We’ll also highlight red flags that mean you should seek care right away. The goal is simple: give practical information that helps you decide whether lifestyle tweaks are enough or whether a medical checkup is a good next step. You’ll see that many solutions fit into dily life—like smarter layering, little bursts of movement, and stress tools—while some conditions need testing and treatment. Read on for our expanded list of science-backed points to help warm your hands and feet and protect your health.

1. Vasoconstriction: Your body's first defense

When you step into cold air, your body reacts almost immediately. Small muscles around tiny blood vessels in your hands and feet tighten. This narrowing, known as vasoconstriction, reduces blood flow to the skin so heat stays near vital organs. The autonomic nervous system controls this reflex automatically, using hormones and nerve signals to coordinate the response. That’s helpful during brief exposures to cold because it maintains blood pressure and core temperature. But if these vessels are overly reactive, or if blood flow is already reduced for other reasons, the normal reflex becomes uncomfortable and persistent. Stress, anxiety, and caffeine can amplify vasoconstriction through adrenaline and other signals. Over time, repeated or prolonged constriction may cause numbness, aching, or slowed healing in the fingertips and toes. Understanding that vasoconstriction is a protective, automatic action helps remove worry while pointing to sensible remedies—like gradually warming up, avoiding sudden cold exposure, and using relaxation tools to calm the nervous system. If narrowing happens frequently without clear triggers, a medical check can help find underlying causes and options to ease symptoms.

2. Why hands and feet chill faster

Hands and feet lose heat faster than the trunk for a few practical reasons. Their surface area relative to volume is high, meaning heat escapes quickly from fingers and toes. They’re also farther from the heart, so blood has to travel longer distances through small vessels that are easily influenced by temperature and nerves. In addition, the skin on fingers and toes is thinner and often has less insulating fat than other parts of the body. Those features combine so that even modest drops in blood flow translate into a big change in how warm your extremities feel. Another factor is local metabolism—muscle and tissue in the hands and feet generate less heat at rest than larger muscle groups. That’s why simply moving your fingers or toes can produce a noticeable warming effect: muscle activity increases local blood flow and heat production. If you spend long periods sitting, or if your footwear is tight, mechanical restrictions can further limit circulation. Recognizing these ordinary reasons can help you choose simple fixes, like frequent micro-movements and thoughtful clothing choices, especially when you’re dealing with colder weather or long sedentary spells.

3. Raynaud's phenomenon: exaggerated vessel spasm

Raynaud’s phenomenon is a common reason people notice dramatic coldness in fingers and toes. In Raynaud’s, small blood vessels overreact to cold or emotional stress and briefly spasm, cutting off flow to the skin. A classic sign is a three-stage color change: pale or white, then blue as oxygen drops, followed by red as blood returns. NHS Scotland and other medical sources describe two types: primary Raynaud’s—generally harmless and often starting in younger adults—and secondary Raynaud’s, which is linked to other conditions like autoimmune disease. Up to about 20 percent of adults may experience Raynaud’s symptoms, and while many cases are mild, secondary Raynaud’s can cause more serious issues such as ulcers or skin changes. Triggers vary by person and include chilly environments, handling cold objects, and emotional stress. Self-help measures—keeping warm, wearing gloves, and avoiding sudden cold—are first-line. For frequent or painful attacks, clinicians can evaluate for underlying causes and consider treatments ranging from behavioral steps to medications that relax blood vessels. If color changes are severe or sores appear, seek medical advice promptly.

4. Peripheral artery disease (PAD): blocked flow in larger vessels

Peripheral artery disease, or PAD, is a condition where larger arteries outside the heart and brain become narrowed by atherosclerosis. When arteries in the legs or arms stiffen and narrow, tissues downstream receive less blood, which can make feet or hands feel persistently cold. PAD often causes pain when walking, known as claudication, because muscles demand more blood during activity. It also slows wound healing and raises the risk of ulcers or infections in the lower extremities. Because PAD signals systemic vascular disease, its presence increases the risk of heart attack and stroke. Diagnosis typically includes a physical exam and tests such as the ankle‑brachial index, which compares blood pressure in the ankle and arm, and Doppler ultrasound to visualize flow. Treatment focuses on reducing cardiovascular risk—quit smoking, control blood pressure and cholesterol, manage diabetes—and on improving circulation through supervised exercise programs and, in some cases, procedures to open blocked arteries. If you notice persistent coldness with leg pain or non-healing sores, seeing a vascular specialist is important for timely care.

5. Diabetes and nerve damage that masks circulation problems

Diabetes affects both nerves and small blood vessels in the feet and hands, creating a double challenge for warmth and sensation. High blood sugar over time damages nerve fibers, producing neuropathy that can make feet feel numb, tingly, or cold even when surface temperature isn’t dramatically low. At the same time, small vessel damage reduces blood flow to the skin, compounding the sensation of chill. People with diabetes also have higher risk of infections and slower wound healing, so a cold, numb foot can hide a wound that becomes serious. Routine foot exams, good glucose control, and daily self-checks for cuts, blisters, or color changes are practical ways to reduce risk. A healthcare provider may run vascular tests or nerve studies when symptoms are new or concern exists. Simple daily habits—proper footwear, gentle foot movement, and protective socks—help maintain circulation, while medical interventions may be needed for significant blood-flow problems. If you have diabetes and you find numbness or persistent cold in your feet, mention it to your clinician so they can include vascular and neuropathy checks in your care plan.

6. Thyroid slowdown: low metabolism, low warmth

Your thyroid gland helps set metabolic pace, and when it runs slowly—hypothyroidism—many people feel cold more often. A lower metabolic rate reduces the heat produced by cells, so hands and feet can feel colder even if overall body temperature is normal. Other signs that point to an underactive thyroid include fatigue, weight gain, dry skin, and sensitivity to cold. Because hypothyroidism is diagnosed with straightforward blood tests that measure thyroid hormones and related markers, testing is often part of the evaluation when someone complains of persistent cold intolerance. Treatment with prescribed thyroid replacement typically restores metabolic balance and often improves cold sensitivity over weeks to months. If you notice new or worsening cold intolerance combined with tiredness or other changes, a primary care visit for basic blood testing is a reasonable step to check thyroid function and rule out treatable causes.

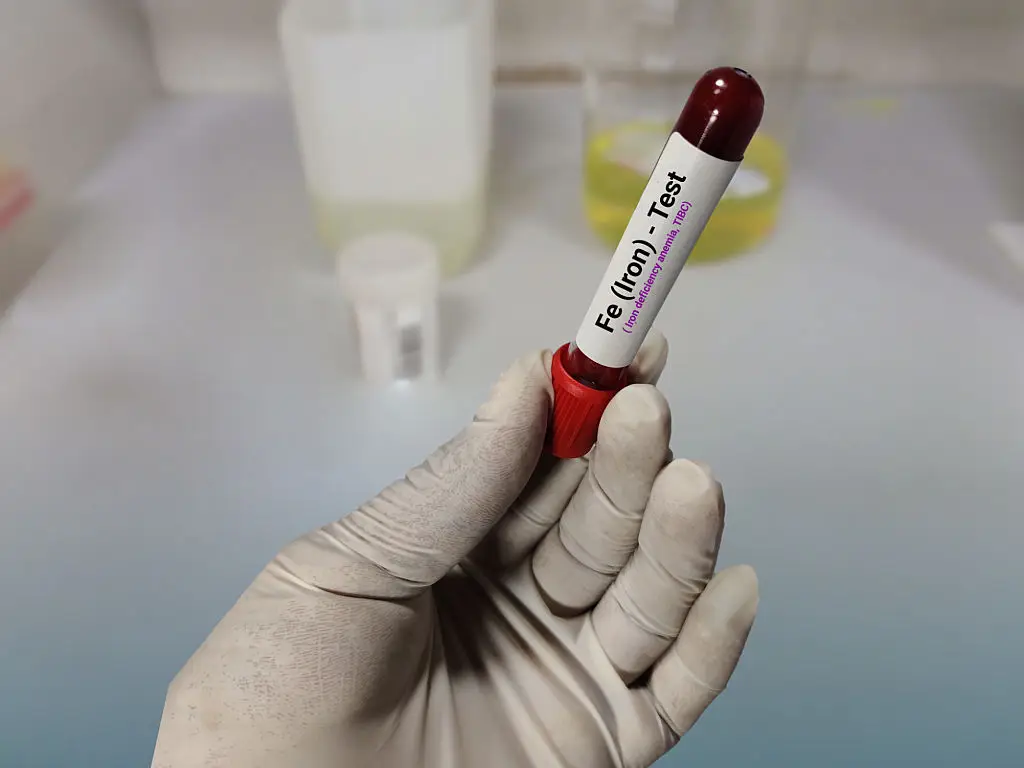

7. Anemia: less oxygen, less warmth

Anemia means your blood carries less oxygen than usual, and that shortage can make hands and feet feel colder. Iron-deficiency anemia is a common type, but other causes include chronic disease or vitamin deficiencies. When oxygen delivery drops, peripheral tissues receive less fuel for generating heat. Typical accompanying signs are paleness, fatigue, and breathlessness on exertion; these clues help clinicians decide on testing. A simple complete blood count and iron studies can identify anemia and its likely cause. Treatment varies by type—iron supplementation for iron deficiency, dietary changes, or addressing blood loss sources—and often leads to improved warmth and energy. Because anemia can have many underlying reasons, evaluating unexplained cold intolerance with basic bloodwork is a practical step, especially when fatigue or other systemic symptoms are present. Addressing anemia also supports broader health, including immune function and physical stamina.

8. Medications, smoking and sedentary habits that reduce circulation

Certain medicines and everyday habits can narrow blood vessels or blunt circulation so extremities feel cold. Over-the-counter decongestants and some migraine drugs tighten vessels, and certain blood-pressure or heart medications may alter peripheral flow. Smoking causes persistent vasoconstriction and damages vessel linings, worsening coldness and raising long-term vascular risk. Extended sitting or crossing legs for long periods reduces muscle pump action that normally helps blood return from the feet. The good news is these are often modifiable. Talk with your clinician about medication side effects before stopping anything; sometimes an alternative drug or adjusted timing reduces symptoms. Quitting smoking is one of the most impactful changes for improving peripheral circulation and overall cardiovascular health. Simple movement breaks—standing every 30 minutes, marching in place, or ankle pumps—stimulate blood flow quickly and can be done anywhere. Small changes in daily routines often make a big difference to how warm your hands and feet feel.

9. Red flags: symptoms that need prompt medical attention

Most chilly fingers or toes are manageable at home, but some signs mean it’s time to see a clinician without delay. Seek immediate help if an extremity becomes suddenly and persistently cold, numb, or pale, especially with severe pain; these could be signs of an acute loss of blood flow. Non-healing sores, black or darkened tissue, spreading redness, or signs of infection such as fever require urgent evaluation. Also get prompt care if coldness comes with chest pain, breathlessness, or fainting, since those symptoms may signal a broader cardiovascular issue. For people with diabetes, any wound or persistent cold area on the foot should prompt quick medical attention because of higher risk of complications. If you’re unsure whether a sign is urgent, contacting a primary care office or nurse hotline for advice is a sensible step—early assessment often prevents complications and speeds recovery when a vascular problem is involved.

10. How doctors diagnose circulation problems

Diagnosing why extremities feel cold starts with a careful history and physical exam. Clinicians will ask about timing, triggers, color changes, pain, wounds, medications, and other health conditions. Common office tests include the ankle-brachial index (ABI), which compares blood pressure in the ankle and arm to look for PAD, and Doppler ultrasound to visualize blood flow in arteries and veins. For suspected Raynaud’s, doctors may observe attacks and can order blood tests to check for autoimmune disease when secondary causes are suspected. Blood tests also screen for anemia, thyroid dysfunction, and diabetes, which are common contributors. In some situations, more detailed imaging—like CT angiography—helps plan interventions. The advantage of a stepwise diagnostic approach is that many causes are treatable or manageable once identified. If symptoms are new, severe, or accompanied by wounds or other concerning signs, a timely evaluation helps the clinical team choose the most effective tests and treatments for your situation.

11. Treatment and everyday fixes that really help

Treatment depends on the cause, but many practical steps work across conditions and are easy to fold into daily life. Start with warmth and layers: gloves, warm socks, and insulating footwear are simple first steps. Active warming through gentle exercise—hand squeezes, ankle pumps, short walks, or five-minute movement breaks—boosts local blood flow and raises skin temperature. Stress reduction techniques such as deep breathing or progressive muscle relaxation reduce sympathetic nervous system activity and can lower spasm frequency in sensitive people. Smoking cessation and regular aerobic activity improve vascular health over weeks to months. For medically diagnosed conditions, specific therapies exist: calcium-channel blockers like nifedipine may reduce Raynaud’s attacks, while PAD may require supervised exercise therapy, medications for cholesterol and blood pressure, or vascular procedures when needed. Diabetes and thyroid issues are managed medically, and addressing anemia involves targeted treatment. Work with your clinician to combine practical at-home measures with medical care when appropriate. Small, consistent habits often add up to measurable improvement in warmth and comfort.

12. Acrocyanosis: Persistent but Benign Blueness

Acrocyanosis is a condition often confused with Raynaud’s, characterized by persistent, painless blue or purple discoloration of the hands and/or feet, especially in cold weather. What it is: Unlike Raynaud’s, which involves spasms and a sharp, three-phase color change, Acrocyanosis is thought to be a continuous constriction of small arteries, often due to an imbalance in the autonomic nervous system. Why it's unique: The blueness (cyanosis) doesn't typically clear rapidly upon warming and is generally considered benign, not leading to tissue damage. It's more common in women and typically resolves naturally. Action: Doctors diagnose it clinically based on the continuous discoloration and lack of pain. Management is entirely focused on lifestyle: consistent warming, wearing layers, and avoiding cold exposure, as medications are usually ineffective.

13. Buerger's Disease: Smoking-Related Vascular Damage

Buerger’s disease (Thromboangiitis Obliterans) is a rare but serious type of vascular inflammation primarily affecting small and medium-sized arteries and veins in the hands and feet. What it trains: This condition leads to the formation of blood clots that completely block vessels, causing severe pain, coldness, and often leading to gangrene and tissue loss. Why it's unique: It is almost exclusively found in individuals who use tobacco products (including smoking or chewing). Action: Diagnosis relies on ruling out other causes of vascular blockage. The only definitive treatment is complete and immediate cessation of all tobacco use, which often halts the disease's progression. This is a critical red flag, demonstrating the extreme damage smoking can inflict directly on peripheral circulation.

14. B12 Deficiency: Neurological Chill and Circulation

Deficiency in Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) can cause cold hands and feet through two intertwined mechanisms: anemia and nerve damage. The lack of B12 can lead to megaloblastic anemia (large, fragile red blood cells), reducing the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood, resulting in chill. Additionally, B12 is crucial for nerve health; a deficit can cause peripheral neuropathy, leading to abnormal cold or tingling sensations even when the skin temperature is normal. Action: Diagnosis is confirmed via simple blood tests. Treatment involves B12 supplementation (oral or injections), which can reverse the neurological and circulatory symptoms if caught early, restoring normal sensation and warmth over time.

15. Chiari Malformation: Central Nervous System Influence

Chiari Malformation is a structural defect where brain tissue extends into the spinal canal, potentially putting pressure on the brainstem and spinal cord. Why it's unique: This is a central nervous system cause, not a primary vascular problem. The brainstem controls autonomic functions, including temperature regulation and circulation. When this control center is compromised, it can disrupt the nerve signals responsible for vasoconstriction and temperature sensing throughout the body, leading to unexplained, persistent coldness in the extremities. Action: Often discovered incidentally via MRI. Diagnosis is followed by neurological evaluation. While treatment for the malformation varies, understanding this cause shifts focus from peripheral vessels to central nervous system regulation.

16. Cold Immersion (Ice Water Challenge): Acclimatization and Risk

The way your body reacts to acute cold stress, like plunging hands into ice water, reveals your level of vascular health and cold acclimatization. What it trains: This is a diagnostic and sometimes training tool. The speed and severity of vasoconstriction (measured by changes in finger temperature) can help diagnose primary Raynaud’s or assess overall vascular reactivity. Why it's unique: Conversely, athletes or those engaged in Wim Hof-style training deliberately use short-term cold immersion to try to modulate their nervous system. Research suggests controlled cold exposure may improve the flexibility of the sympathetic nervous system, potentially reducing exaggerated vasoconstriction over time. Action: Use this as a self-check only (never if Raynaud's is severe or secondary); otherwise, clinicians use it to gauge baseline vascular response.

17. Hyperhidrosis: Sweat and the Evaporative Chill

Hyperhidrosis, or excessive sweating, can be an indirect but significant cause of chronic coldness in the extremities. What it is: The sympathetic nervous system overstimulates sweat glands, causing hands and feet to be persistently damp. Why it's unique: While the initial cause is heat, the dampness creates a constant cycle of evaporative cooling. Even in a normal environment, the evaporation of sweat rapidly draws heat away from the skin, mimicking the effect of cold air and triggering reflex vasoconstriction. Action: Doctors often diagnose based on history and may recommend clinical-strength antiperspirants, iontophoresis, or, in severe cases, Botox injections to control sweating. Managing the underlying hyperhidrosis stops the evaporative cooling loop, allowing the extremities to retain natural warmth and break the cycle of reflexive chill.

18. Erythromelalgia: The Burning Paradox

Erythromelalgia (EM) is a rare condition that presents as a confusing paradox: the extremities feel intensely hot and burning, yet the underlying issue is related to abnormal blood vessel behavior. What it is: EM involves sporadic episodes of intense heat, redness, and excruciating burning pain, most commonly in the feet. Why it's unique: The affected areas may be triggered by warmth or exercise, but the relief comes from cooling, which ironically can trigger a protective reflex that makes them feel profoundly cold later on. It is essentially an extreme form of vasodilation/vasoconstriction dysfunction. Action: Diagnosis is challenging and relies on clinical presentation. Management often involves cooling the limbs (avoiding ice), specific medications, and managing pain, highlighting a complex and opposite presentation to the common "cold feet" complaint.

19. Dysautonomia: The Miscommunication of Warmth

Dysautonomia is an umbrella term for conditions where the autonomic nervous system—the command center for "automatic" functions like heart rate and blood pressure—fails to communicate correctly with the rest of the body. What it trains: In a healthy system, the nerves tell blood vessels exactly when to constrict or dilate to maintain a perfect internal temperature. In dysautonomia, these signals become erratic or delayed. Why it's unique: You might experience "temperature dumping," where your hands and feet feel ice-cold while your face feels flushed, or vice-versa. Because the system can't stabilize, you might find that simple changes in posture, like standing up too quickly, trigger a rush of blood away from the extremities, leaving them chilled and tingly. Action: Doctors typically diagnose this through specialized testing like a "Tilt Table Test." Management focuses on increasing fluid and salt intake (under medical supervision) to boost blood volume, and wearing compression garments to manually assist circulation when the nervous system falters.

20. Gut Health and the Microbiome's Influence on Circulation

The health of your digestive system might seem unrelated to the temperature of your toes, but the connection lies in systemic inflammation and nutrient absorption. An imbalanced gut microbiome—a condition known as dysbiosis—can lead to a "leaky gut" where inflammatory compounds (endotoxins) enter the bloodstream. This chronic low-grade inflammation signals danger to the body, contributing to the systemic thickening and stiffening of blood vessels (atherosclerosis) that ultimately hinders smooth circulation to the extremities. Furthermore, conditions like Celiac disease, Crohn's disease, or even simple nutrient malabsorption due to poor gut health can lead to deficiencies in B12, iron, and folate—all key components required for healthy blood (anemia), directly causing cold intolerance. Focusing on a diverse diet rich in fiber and fermented foods supports a healthy gut lining, reduces systemic inflammation, and ensures optimal absorption of the micronutrients essential for robust blood flow and heat production.

21. Dysautonomia: The Miscommunication of Warmth

Dysautonomia is an umbrella term for conditions where the autonomic nervous system—the command center for "automatic" functions like heart rate and blood pressure—fails to communicate correctly with the rest of the body. In a healthy system, the nerves tell blood vessels exactly when to constrict or dilate to maintain a perfect internal temperature. In dysautonomia, these signals become erratic or delayed. You might experience "temperature dumping," where your hands and feet feel ice-cold while your face feels flushed, or vice-versa. Because the system can't stabilize, you might find that simple changes in posture, like standing up too quickly, trigger a rush of blood away from the extremities, leaving them chilled and tingly. Doctors typically diagnose this through specialized testing like a "Tilt Table Test." Management focuses on increasing fluid and salt intake (under medical supervision) to boost blood volume, and wearing compression garments to manually assist circulation when the nervous system falters.

22. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS): Positional Nerve Pinch

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS) is a condition where nerves or blood vessels between the collarbone and the first rib become compressed. What it is: While often causing pain or numbness in the arms, TOS can also lead to persistent coldness in the hands and fingers. This is because the compression can irritate the sympathetic nerves that control vasoconstriction, causing them to signal the blood vessels to constrict excessively, or because the artery itself is pinched. Why it's unique: The coldness is often positional, worsening when lifting the arm overhead or carrying heavy objects. Action: Diagnosis involves physical maneuvers (like the Adson test) and sometimes imaging. Treatment usually starts with physical therapy to improve posture and strengthen muscles around the shoulder, relieving the pressure on the structures in the thoracic outlet.

23. Folate (Vitamin B9) Deficiency: Flawed Fuel Delivery

While general anemia is discussed, cold extremities can be a sign of a specific type of anemia—megaloblastic anemia—caused by a lack of Folate (Vitamin B9) or B12. What it is: Folate is essential for producing healthy red blood cells (RBCs). A deficiency causes RBCs to become abnormally large and inefficient at carrying oxygen, leading to reduced oxygen and heat delivery to the hands and feet. Why it's unique: This is often tied to poor diet, malabsorption issues (like celiac disease or alcoholism), or certain medications, even if iron levels are normal. Action: Diagnosis is confirmed by a simple blood test measuring folate levels. Treatment involves increasing intake of folate-rich foods (like liver, spinach, and fortified cereals) or supplementation. Addressing this deficiency quickly restores proper oxygen transport and helps resolve the peripheral coldness.

24. Circadian Rhythm Disruption: The Core Temperature Signal Loss

Your hands and feet naturally warm up shortly before you fall asleep and cool down upon waking. This temperature shift is not random; it's a vital, centrally regulated component of your circadian rhythm (your 24-hour internal clock) that signals to your body when to initiate sleep and when to increase alertness. Disruption, caused by shift work, inconsistent sleep schedules, or excessive blue light exposure at night, scrambles these signals. When the brain can't reliably read the internal clock, its regulation of peripheral blood flow—the subtle vasodilation and constriction needed to maintain comfortable extremity temperature—becomes erratic. This can result in persistent, unexplained coldness or temperature dysregulation throughout the day. Action: Doctors advise strict adherence to a consistent sleep schedule and light hygiene (avoiding screens an hour before bed) to stabilize the master clock, allowing the autonomic nervous system to regain proper, predictable control over peripheral circulation.

25. Popliteal Artery Entrapment Syndrome (PAES): A Muscle-Bound Vascular Trap

Popliteal Artery Entrapment Syndrome (PAES) is a rare cause of coldness and pain in the feet and lower legs, particularly in young, otherwise healthy athletes. What it is: Instead of a vascular blockage (like PAD), PAES is a mechanical issue where the calf muscles (specifically the gastrocnemius) are positioned abnormally, or are excessively large, causing them to periodically squeeze or entrap the main artery behind the knee (the popliteal artery). Why it's unique: The blockage and resulting coldness typically occur only during active exercise or movement, immediately ceasing upon rest. Over time, this repeated compression can cause damage or fibrosis inside the artery. Action: Diagnosis often requires a vascular ultrasound performed while the patient actively flexes their calf muscle. Treatment usually involves surgery to free the artery from the compressing muscle.

26. Adie's Syndrome: The Pupils and Peripheral Flow Connection

While primarily known as a neurological condition affecting the eye, Adie's Syndrome (or Holmes-Adie Syndrome) can provide a rare but fascinating explanation for persistent coldness in the extremities. It is caused by damage to the postganglionic fibers of the parasympathetic nervous system, typically resulting in one pupil that stays dilated and reacts slowly to light. However, because the autonomic nervous system is a highly interconnected web, this localized damage is often accompanied by broader autonomic dysfunction, including abnormal sweating and impaired vasomotor control. In these individuals, the "thermostat" signals that manage the dilation and constriction of blood vessels in the hands and feet become uncoordinated or sluggish. This leads to periods where the body fails to properly warm the skin, leaving the limbs feeling ice-cold even in mild temperatures.

27. Cryoglobulinemia: The Protein "Gelling" Effect

Cryoglobulinemia is a rare but medically significant condition where specific proteins in the blood—called cryoglobulins—become insoluble and clump together (or "gel") when body temperature drops. This is not a simple muscle spasm like Raynaud’s; it is a physical thickening of the blood itself within the small vessels of the hands and feet. These protein clumps can block blood flow, leading to intense coldness, purple skin spots (purpura), and even joint pain. It is often a secondary symptom of underlying issues like chronic infections (such as Hepatitis C) or certain immune system disorders. Doctors diagnose this by taking a blood sample and literally cooling it in a lab to see if the proteins precipitate. Treatment focuses on addressing the underlying cause and strictly avoiding cold triggers to prevent the blood from "thickening" in the extremities.

28. Hypotension: Low Pressure, Low Heat Delivery

While much focus is placed on blocked or spasming vessels, sometimes the issue is simply a lack of "push" from the heart. Chronic low blood pressure, or hypotension, means the force moving blood through your system is weaker than average. Since the hands and feet are the furthest points from the pump, they are the first to lose out when pressure drops. This is especially common in very lean individuals or those with certain cardiovascular or endocrine conditions. Without enough pressure to drive warm blood into the smallest capillaries of the fingertips, the extremities remain perpetually chilled. Doctors often investigate hypotension if cold extremities are accompanied by dizziness or fainting. Management usually involves increasing fluid and salt intake or wearing compression stockings to help return blood to the heart and maintain higher systemic pressure.

29. Sjogren’s Syndrome: The "Dry and Cold" Connection

Sjogren’s syndrome is an autoimmune condition primarily known for causing dry eyes and a dry mouth, but it frequently involves the vascular system in a way that leaves hands and feet perpetually chilled. In Sjogren’s, the body’s immune system attacks its own moisture-producing glands, but it also commonly triggers secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon. What makes this unique is that the inflammation can extend to the small blood vessels themselves (vasculitis), causing them to become thickened or narrowed. This physical change in the vessel wall, combined with an overactive nervous system response, creates a persistent state of low blood flow. If you experience cold extremities alongside gritty-feeling eyes, a persistent dry cough, or joint pain, it may point toward this systemic issue rather than simple sensitivity to temperature. Doctors diagnose Sjogren's through specific antibody blood tests (such as Anti-SSA and Anti-SSB) and occasionally a lip biopsy. Management involves systemic anti-inflammatory treatments and meticulous protection from cold to prevent tissue damage.

30. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS): The Nerve-Vessel Misfire

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is a chronic condition that usually develops after an injury, surgery, or stroke, but the subsequent pain is out of proportion to the original event. What makes it a unique cause of cold extremities is the "warm-to-cold" transition. In the "cold" stage of CRPS, the affected limb (usually a hand or foot) becomes significantly colder than the rest of the body due to severe, localized autonomic dysfunction. The nerves incorrectly signal the blood vessels to stay in a state of permanent, tight constriction. This results in skin that appears bluish or pale, feels icy to the touch, and may even show changes in hair or nail growth. Unlike standard circulation issues, CRPS is often accompanied by extreme sensitivity to touch and swelling. Doctors typically use a combination of physical exams and bone scans for diagnosis. Treatment often requires a multidisciplinary approach, including specialized physical therapy and nerve blocks, to "retrain" the nervous system to allow normal blood flow to return to the limb.

Takeaway: practical steps and when to get help

Cold hands and feet are a common experience with roots in normal physiology and in medical conditions. The body narrows vessels in extremities to protect the core, which explains why fingers and toes feel chilly first. Often simple habits—layering, movement, stress tools, and quitting smoking—bring relief and protect long-term health. However, persistent or severe coldness, dramatic color changes, pain, non-healing sores, or sudden loss of warmth are red flags that deserve prompt medical attention. Basic tests in primary care can check for treatable causes like anemia, thyroid problems, diabetes, Raynaud’s, or peripheral artery disease, and targeted treatments are available for each. Our advice is practical and realistic: start with gentle self-care and pay attention to warning signs. If symptoms are new, worsening, or accompanied by other concerning features, make an appointment to get evaluated. With the right mix of lifestyle changes and medical care when needed, most people find meaningful improvement and regain comfort in their hands and feet.