How Immunotherapy Is Used To Treat Cancer

Cancer causes unrestrained cellular proliferation and growth, and in some cases, cancer cells can hide from or compromise the body’s immune system, which is designed to fight off infections and illnesses. This is one of many reasons why cancer is such a devastating and dangerous disease.

One of the rising treatment methods for cancer, however, is immunotherapy, a type of biological therapy. It is used to restore the immune system or greatly boost its normal functionality. Immunotherapy can introduce new elements to the body’s immune system or stimulate what is already there to help the immune system better destroy cancer cells. It can slow and stop the growth and spread of cancer, as well as effectively deliver radiation or chemotherapy to the cancer cells directly.

Methods Of Immunotherapy

Patients can receive immunotherapy in approximately four different ways. The two most common methods are oral, in which the patient swallows a pill, and intravenously, where the doctor administers immunotherapy through a needle inserted into one of the patient’s veins. There are also topical immunotherapies, which is where the patient rubs cream into their skin. Topical treatment is usually for early stages of skin cancer. Finally, there is intravesical immunotherapy, where the treatment goes directly into the bladder (specifically used to treat bladder cancer).

Cycles Of Immunotherapy

The length of time a patient receives immunotherapy for cancer treatment, as well as how often they receive this treatment, all depends on their individual case. Factors doctors consider include the type of cancer being treated, how advanced the cancer is, the type of immunotherapy being given, as well as how the patient’s body reacts to the treatment. Patients can receive treatment as often as once a day.

Many immunotherapies are administered in what doctors call cycles, which means there is the treatment followed by a rest period. The purpose of the rest period is to allow the patient’s body to recover from and respond to the treatment, and build healthy cells. The rest period is also a good time for the doctor to assess the effectiveness of the treatment and adjust as necessary.

Monoclonal Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are man-made antibodies and are designed to trigger a reaction from the body’s immune system, just like natural antibodies. Some cancers, such as breast cancer, exhibit antigens on the surface of cancer cells. These antigens are what some monoclonal antibodies will attach themselves to, which indicates the immune system needs to attack and destroy them.

Doctors will also use monoclonal antibodies as a targeted therapy for cancer since they can block abnormal proteins in cancer cells. They can also block growth signals and thus prevent cancer from growing. Monoclonal antibodies are also one of the types of immunotherapy able to deliver chemotherapy or radiation straight to the cancer cells.

Types Of Monoclonal Antibodies

There are three major types of monoclonal antibodies: naked, conjugated, and bispecific. Naked mAbs, the most popular, work independently and do not require attachment onto any drug or radioactive material. They can attach themselves to the antigens located on the cancer cells, to antigens on non-cancerous cells, or to free-floating proteins. Conjugated mAbs are bound to a radioactive particle or chemotherapy drug and are then used as a mechanism to transfer the drug (e.g., chemotherapy) to the cancer cells to kill them.

The final type, bispecific mAbs, are comprised of two different mAbs. Due to this, they can bind to two different proteins simultaneously. By attaching to the two proteins, the drug unifies the cancer cells and immune cells, which research indicates as a trigger for the immune system to attack the cancer cells.

Adoptive T-Cell Therapy

Adoptive T-cell therapy attempts to boost the body’s natural ability to fight cancer. Specifically, it does this through the body’s T cells, a certain type of white blood cell. These cells contain receptors, which are their own proteins. These bind to foreign antigens, triggering the immune system to destroy foreign particles. In this treatment, doctors will take T cells harvested from a cancerous tumor to the lab and modify them so they are better able to spot foreign antigens and specific cancer cells. This process can take anywhere from two to eight weeks, at which point they are reintroduced to the body through a needle.

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

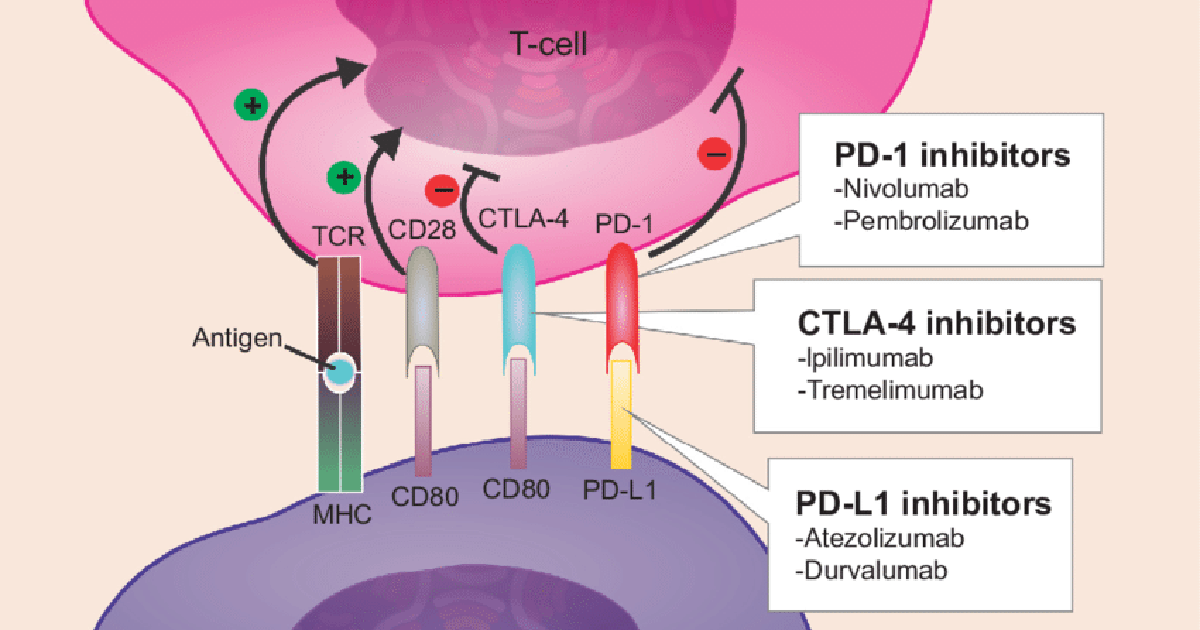

The immune system must be able to identify the difference between normal and foreign cells, as this allows it to target the foreign cells while leaving normal cells untouched. Every immune system does this by creating checkpoints, which act as stop signals to keep the body in check and trigger (or prevent) an immune system response. Unfortunately, cancer can often find ways to prevent being attacked by modifying the checkpoints, such as creating premature stops. This is where immune checkpoint inhibitors — which target PD-1, PD-L1, or CTLA-4 — come into play.

PD-1 is a T cell checkpoint protein preventing the T cell from attacking other non-cancerous cells in the body by acting as an off-switch when it attaches itself to PD-L1, another protein on some cells. However, some cancer cells contain PD-L1, which allows them to avoid immune attack. PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors stop the binding to cancer cells and boost the immune system’s attack response. CTLA-4 is another protein that acts as an off switch in the body. CTLA-4 inhibitors are designed to bind to CTLA-A and prevent its function, which boosts the immune system’s response.

Oncolytic Virus Immunotherapy

The Cancer Research Institute indicates this treatment is not currently FDA-approved, though there are clinical trials using oncolytic viruses to treat many cancers, including bladder, prostate, ovarian, lung, colorectal, and melanoma. This immunotherapy technique uses various types of viruses to boost the immune system’s activity against cancer. Oncolytic viruses are specifically intended to kill cancer cells and can either do this directly or activate the immune system (e.g., through T cells and dendritic cells) to perform this function. This form of immunotherapy is often combined with other immunotherapies, commonly mAbs and cancer vaccines, for cancer treatment.

Cancer Vaccines

When most individuals hear the word ‘vaccine,’ they think of the flu shot or one of the many children receive, such as vaccines for measles, mumps, and polio. Typically, these vaccines use a weakened or deactivated form of the virus so the body gets ready for an immune response and can better fight off the illness. Cancer vaccines work in much the same way. They either get the immune system ready to attack cancer cells or they act as a preventative measure.

A prime example of a preventative cancer vaccine is the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. HPV can cause various cancers, the most significant of which is cervical cancer, which is almost exclusively due to an HPV infection. But by receiving the HPV vaccine, the chances of getting an HPV infection dramatically reduce, particularly if the individual receives the vaccine prior to becoming sexually active for the first time. Cancer treatment vaccines, on the other hand, work to make the immune system attack cancer cells already in the body. According to the American Cancer Society, the only cancer treatment vaccine currently approved in the United States is Sipuleucel-T, which is used to treat advanced prostate cancer.

Common Side Effects Of Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy, like any other treatment, comes with potential side effects, though most are mild and taper off once the body adjusts to the treatment. Additionally, side effects from immunotherapy tend to be fewer than those from other cancer treatments. The side effects patients experience and their severity depend on the type of immunotherapy treatment or combination of treatments, the dosage, how the patient is receiving the treatment (e.g., orally or intravenously), and the patient’s overall health.

The most common side effects all fall under the ‘flu-like’ classification, and include fever, chills, nausea, loss of appetite, as well as body aches and pains. These symptoms tend to occur shortly after receiving the immunotherapy treatment. Reports indicate taking medicine such as acetaminophen and receiving immunotherapy before bed can help the body adjust and minimize these symptoms. Other side effects include fatigue, which often accompanies the flu-like symptoms, and skin reactions, such as itchy skin, redness, swelling, or a rash. Patients should inform their doctors of any side effects so they can adjust dosages, prescribe medicines, or change the immunotherapy treatment as needed.

Serious Side Effects Of Immunotherapy

Some of the rarer side effects of immunotherapy used in cancer treatment include trouble breathing, high or low blood pressure, a weakened immune system, increased risk of infection, as well as severe or even fatal allergic reactions. Doctors understand the potential effects and would weigh the options before recommending treatment to a patient. It is especially important for patients to fully disclose their medical history, including information on allergies, medications they have taken, as well as family medical history. All of this information helps doctors prescribe immunotherapy treatments with the lowest chances of causing serious side effects while also balancing the effectiveness.

Doctors will also, of course, run through the specific side effects patients need to watch out for once they recommend a particular immunotherapy treatment, since the potential effects do shift. As with the common side effects, patients should report any unusual symptoms when receiving immunotherapy immediately.